Developing into the Unknown by Using Performance: Observing the Air Plant: Performance Ability within Contemporary Arts Exhibition

Man-Nung CHOU

Will the concept of performance unfold and grow? Art museums and exhibitions introduce the idea of “performance” and “performance-oriented activities and events,” in which performance is developed into an exhibition item. By contrast, the notions of “exhibition” and “integrating exhibition performance and activities in space” are incorporated into theaters or shows. Subsequently, art boundaries begin to blur and vanish and invade new grounds, facilitating the emergence of new ideas. The goal of contemporary art has arguably transcended the superficial attempt to “integrate visual exhibitions and show elements to give birth to new artwork types”; that is, the concepts of “eventization” and “mediumization” are also explored:

(1) “Eventization” (i.e., creating events) and “mediumization” (i.e., offering mediums) enable the audience to become involved with the development and completion of artworks. By transforming the cooperation models used during the art creation process, art creators are no longer the sole owners and “aesthetic authorities” of their artworks, and ideas conveyed by their artworks are transmitted in a bidirectional (rather than unidirectional) manner. In addition, performance becomes a core concept and practice that challenges existing systems, exhibitions that are “playing it safe,” and the relationships between exhibitions and their participants. Eventization and mediumization signify multiple facets, multiple dimensions, and the possibility of new perceptions and viewing experiences, facilitating subsequent exchanges and creating new meanings. The ideas of eventization and mediumization have been incorporated into the artwork plan (dispositif) and game rules at the very beginning of the Air Plant: Performance Ability within Contemporary Arts exhibition (hereafter referred to as the Air Plant exhibition).

(2) This does not mean that artworks must invite the audience to take part in them or perform for the artworks to embody performance ability. The re-exploration and planning of mediums such as designing and uniting artworks and exhibition space, presenting artists’ statements, expressions, and strategies, and holding a series of related lectures, workshops, and activities are all a part of achieving “eventization” and “mediumization” and realizing the goal of performance. In other words, finalized artworks or exhibitions are not the only places to find performance, and artworks and events that communicate the idea of performance are not the only objects and events that can be called performance. The term “performance” has been widely understood, used, and claimed, offering new possibilities for interpreting the concept. However, an overuse of the term will result in it becoming an idea without substance because not all artists thoroughly consider the concept during the initial artwork and event creation stage. As the concept becomes a trend, the question “What is the reason for artworks to perform?” needs to be answered.

(3) Actual practices that attempt to answer the aforementioned question can be observed, where the practices focus on investigating the various “mechanisms” (i.e., museums and theaters) in place. In addition, existing art classifications and boundaries are questioned. The following questions are raised: What more can museums do? What more can theaters do? What new possibilities can exhibitions and performances offer? Actual practices are implemented to challenge the dimensions of concepts, imaginations, and implementations. Furthermore, a variety of issues are incorporated into artworks and events.

The aforesaid issues are also observed in the Air Plant exhibition, an exhibition hosted by the National Taiwan University of Arts (NTUA), curated by Chun-Yi Chang, and exhibited at the NTUA Yo-Chang Art Museum and The Northern Campus. However, contrary to most other exhibitions (e.g., the Arena and Displace exhibitions recently organized by the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (in Taiwan) and the Rockbund Art Museum (in Shanghai), respectively), Air Plant exhibition also presents unique concepts. In the Arena exhibition, a visual art exhibition method was adopted and a long series of performances were delivered to complement the exhibition. The notions of “living exhibitions” and “living objects” were proposed to explore the possible relationships between performances and exhibitions. By contrast, the Displace exhibition (a short and intense exhibition) introduced a new type of exhibition that could not be discerned and the exhibition paid special attention to how audience participation extended and transformed artwork concepts. The two exhibitions emphasized creating art using ones’ experiences “at the moment” and tackled many social issues_. In contrast to these two exhibitions, the Air Plant exhibition is in no hurry to bring performances into the galleries and organizes only a small number of performance-related activities. The exhibition does not seek to discover new ideas from existing art boundaries or declare promising possibilities. Instead, it shows that “performance” is an act of “extraction,” in which objects, devices, mediums, and materials are used to enable material and spatial re-planning (these “re-plans” include the series of workshops held) to open up new viewing and perception possibilities and achieve eventization and mediumization, maximizing the performance ability of artworks.

Our discussion on the performance ability within contemporary arts begins with Christian Rizzo’s Some Events Are Currently Ongoing…

Audience entering the exhibition site will witness an intriguing and perplexing space filled with ball-shaped objects, potted plants, books, a pile of clothes in a cloud of smoke, the words “Not Know” in white, and a piece of clothing “dancing” in the air. Falling lights create a lighting effect similar to that of spotlights, adding a stage-like appearance to the exhibition site. The audience will see the colors and fibers of the light beams as it becomes a part of the installation.

A dark space and specially designed light beams create a venue with unclear boundaries, in which the only discernible boundary is a bright screen showing performances delivered on a stage. Dynamic images of motion development processes, various body parts in motion, and slow movement processes draw the audience’s attention to the performances shown afar, where the audience becomes a part of the stage and is surrounded by the stage.

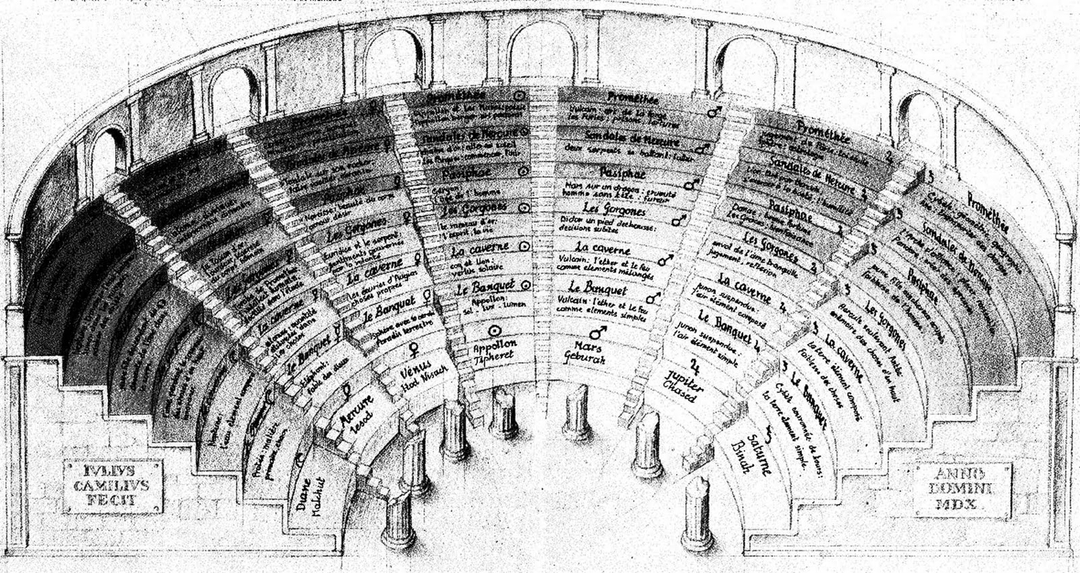

This artwork reminds people of Giulio Camillo’s Theater of Memory, where users (i.e., the audience) stood on a stage and were surrounded by images of knowledge in the universe. Knowledge was presented in a systematic way, and the formation of thoughts and the operations of and connections between knowledge were manipulated by the audience_. Contrary to the Theater of Memory, which featured clarity and order and developed the theater into an area filled with thoughts and cognition, Some Events Are Currently Ongoing… is darker. In addition, no pre-established centers are in place and the connections (including no connections) formed by the interaction between objects and images create an overall environment without a center. This phenomenon matches the name of the artwork “Some Events Are Currently Ongoing…” and illustrates how events are in an ongoing state that cannot be accurately identified. Thus, instead of being an artwork that is clear, safe, understandable, predictable, and filled with thoughts, it is one that displays the boundaries of thoughts where the comprehensible and the incomprehensible meet, senses and perceptions emerge, and objects and image become indescribable.

A fascinating, eye-catching, but creepy installation can be found in the center of the exhibition site: a human body covered with long hair sitting in a chair. The hair prevents the audience from seeing the element (i.e., facial expressions) that best reveals the human body’s disposition. The human body appears to be a man as well as an object, becoming an entity (referred to as “man–object”) that is neither one of the two but a mix of both. The man–object is in a static reading gesture; however, what he is reading (i.e., a book) shows dynamic human images. Thus, how should the audience interpret this installation? Although this installation seems to be a simulation of Western classical sculpture and human figures, the audience is unable to see its face because it is covered with hair and that its personality traits and subjectivity are removed. Therefore, it is an entity with strong physical features but hollow internal qualities. With the entity reading the book being considered a static state and the item being read being considered a dynamic state (i.e., showing repeated dynamic images that imply continuously changing reading content), how does the act of reading continue?

The paradoxical man–object is an object performing on stage and one that is being watched by the audience. In addition, the man–object offers clues concerning performance and perspective, two concepts conveyed by this artwork/event to inspire the audience to reflect on two dimensions. The first dimension begins with creating an environment without a center (as described above) in which the audience can study artworks freely and affectionately; the dimension then continues with the audience standing in the center of the stage, reversing the roles between artworks and viewers in past exhibitions. The second dimension uses the paradoxical installation to urge the audience to contemplate the questions of viewer and “viewee” (i.e., object being viewed). The first dimension entails the audience using its free subjective awareness and imaginations to deduce the connections between items, whereas the second dimension involves the aggregation of impersonal elements. As exemplified by the image of the man–object, numerous elements interact in a network without a center; as the kinetic energy of a subject between objects increases and the physical characteristics and sensitivity of the body amplify, the audience’s subjective awareness is pushed to the limit that it becomes dim, faint, and even nonexistent. The audience’s perception is merely a temporary existence and a reflux (caused by a variation in speed) in the never-ending flow of time; such a temporary existence is real yet unreal. The second dimension also uses materialized objects to clearly indicate the different perspectives that are present, provoking the audience to re-evaluate their thoughts and awareness to further their understanding of the two dimensions.

The aforementioned dimensions are two essential dimensions found in the “performance ability” preached by the Air Plant exhibition and epitomize the objectives and philosophies of the exhibition. Preaching only the first dimension results in the presentation of only the different roles of “participation” and “relationship” (which are commonly discussed in popular reviews and creative discourse). By contrast, preaching also the second dimension opens the audience’s mind to consider more than its perception and forces it to become aware or think about the existence of boundaries so that it tackles the unknown.

These results illustrate why “performance ability” (rather than “performativeness”) was used to name the Air Plant exhibition. Performance ability is a collection of abilities that have been realized or have the potential to realize; such abilities may not realize or may realize in a manner that differs from people’s expectations. Performance ability questions and explores the unknown rather than offering structural or intrinsic qualities.

3.

The artworks exhibited touch on a variety of ideas such as exploring images and material qualities as well as adding fictitious and implicit narrative context to theater/stage designs and space shaping. If expansion efforts are to be continued, “traces” shall be the key to achieving “performance ability.”

Riverbed Theatre’s I Stand Naked in the Street with Sleeping Lions, found on the second floor of the Yo-Chang Art Museum, is an artwork designed based on the original structure of the exhibition space (Picture 1). The artwork comprises three components, which are a pink theater-like space, a large-scale 2D drawing, and suspended animal bones connected by wires and containing painted patterns. The three components, joined by the idea of “deer,” are three “ways” to look at the artwork and the “windows” of traces and time: the audience can stand closely to the 2D drawing to study its brushwork and damage found its surface, stand closely to observe the suspended animal bones found in the concave area of a wall, and inspect the 3D drawing-like theater space from a distance. Materials used to leave traces (e.g., animal bones) and objects and traces left behind by men after engaging in various activities are time and life-related items that are revitalized when the audience sees them. The dangling stick in the pink theater-like space illustrates the passage of time and a sense of anxiety, where the two concepts cannot be measured and stored quantitatively. The traces of time displayed by the stick and the dead clock on a wall seem to be in a debate about the following time-related questions: “What is the time that we experience?” “Is it really passing?” “Are all moments really that different from others?”

Traces found on the materials are end products when life vanishes and indicate the departure of life. The swaying of the stick creates visual and perceived traces, making the movements of the stick both movements and “traces of movements.” The swaying of the stick also demonstrates the use of self to express oneself and rejects the reproduction and retention of materialistic traces, showing that true life (e.g., time) cannot be expressed or reproduced. For example, even the possession of the various “components” of time (e.g., time sequence and duration (durée)) is unable to allow one to grasp time and life, echoing one of Sigmund Freud’s theories on dreams and reality and on beauty and violence: desire of one’s subconsciousness hidden in everyday life is an untamed beast, which represents both time and life.

Traces are simple yet complex and come in a variety of forms; examples include traces of time, traces of life, traces of minds, and traces of the self-expressions of pure substances and images. Yung-Ta Chang (artwork: Relative Perception N°4-C) uses copper sulfate of varying concentrations to create paint-like traces on heated metal plates; River Lin (artwork: A Day in the Life of the Administrator of Yo-Chang Art Museum) invites the audience to observe traces created by daily life, work, system, and personal life (Picture 2); and La Ribot (artwork: Beware of Imitations!) utilizes a moving camera and the playing of a piano to introduce bodies, music (including a music score) of varying “frequencies,” and control that form image traces. By contrast, Wei-Chia Su (2017) (artwork: FreeSteps–Sense of Place) employs bright, uniform lights and compact surrounding space to form a picture-like display area. Body movements are meticulously and slowly enlarged, in which the intellectual and alienated appearance of the artwork, similar to La Ribot’s blurred and dim artwork, successfully engenders a perceptual trance that disassembles the dance itself (Picture 3 and 4).

Artworks exhibited in The Northern Campus are incorporated into a daily space with a sense of history and life, symbolizing the “re-piecing together” of traces as well as using traces to re-create revitalized space and memories. For example, Ying-Cheng Tsai (artwork: No. 212) reassembles the traces of memories and history to form pure, complete material forms; Jui-Chien Hsu (artwork: Direct) creates a movement and stillness-based paradox, causing the audience to be under the impression that the artwork is constantly moving; Fong-Fong’s Group (artwork: Fong-Fong House) takes actions and uses materials to re-sew physical space; and Joyce Ho and Snow Huang (artwork: 254 Yen) employs objects, sounds documents, and fictional narratives to summon memories of the past. In addition, they engage in a lost-and-found endeavor to create a future event that may or may not happen.

Escaping the control and protection of “white boxes” (i.e., exhibition galleries), outdoor environment-based artworks in The Northern Campus change according to the weather and external conditions they are exposed to during the exhibition, creating new “traces”: Yueh-Nu Kuo’s Layered Space produces a space with traces of white plastics and bodies; Kuei-Chih Lee’s Recycling Scenery presents traces of a landscape struck by an imaginary flood. The scenery inside the artwork skillfully echoes the life of the local area. The ambiance of the area changes with weather, instilling a sense of life in the artwork that seems to breathe and live with the area; and Yen-Hong Liu’s Ceylon Houndstongue and the Realms of Land, Water, Fire, Wind, and Space uses plants to transform the humidity of an old house into a comfortable, visually powerful environment. In addition, by painting visitors’ dreams and exhibiting these paintings, he revitalizes the original space into a relaxing and sharing-oriented area (Picture 5).

In the Yo-Chang Art Museum, Joyce Ho’s These Things That Drift Away introduces three similar and connected white rooms with subtle differences. The subtle differences in time and space are the results of her designs as well as the psychological experiences felt by the audience when visiting the exhibition site. The audience regularly feels that something is different and out of place, causing it to wander back and forth. The artwork evokes an unusual sensation similar to the content shown in exhibition site video (i.e., ink leaking from the pocket of a white shirt that creates a mark that cannot be duplicated). Such a unique moment is adeptly repeated in the other two rooms with slight time differences, prompting the artwork to continue to loop. The feeling of repeats, differences, blurred sense of time, and uncertainties impel the audience to want to get away from the exhibition site; however, it is unable to do so, showing the powerful draw of low profile and imperfection (Picture 6). Ho’s artwork can almost be compared with that of the Riverbed Theatre, which is why the two artworks were selected as the first and last artwork detailed in this section: If the Riverbed Theatre uses a wealth of visuals and various designs of traces to open up a discussion about time and life, then Ho’s artwork uses the coexistence between “gaps” and traces at this moment/instant (including the various differences in space) to bring the artwork closer to the audience, highlighting the uncertainties and inexplicability of life; life is not a beast, but a black hole.

Different from exhibitions that use the audience’s experience “at the moment” to shape its exhibition-viewing experience, the Air Plant exhibition also explores the concept of performance. The exhibition ventures into uncultivated stages and the unknown and examines the traces of time. Concerning the audience’s exhibition-viewing experience “at the moment,” it is empty, hidden, and “back-based,” which creates a force and logic that foster numerous traces and subsequently performance ability. This is the unique atmosphere engendered by the Air Plant exhibition.

We return back to examining the ideas behind the naming of the Air Plant exhibition, which involved expanding on the concepts proposed by Gilles Deleuze (i.e., rhizome) and Nicolas Bourriaud (i.e., radicant). Air plants can survive without soil and adapt to the environment in which they are in, signifying free and active art creations and the use the gaps between cultures and domains to create new possibilities. The author of this article also experiences the use of “traces” and “emptiness” to form new dimensions and facets at the Air Plant exhibition. Such a method of exhibition and operation offers new options and potential. Will this method lead to the concept of boundary being reinvented or abandoned? That remains to be seen.

To answer the first question of this article (i.e., “What is the reason for artworks to perform?”), in addition to questioning various art systems and issues, we must reflect on questions such as “What more can art be or do?” Only by venturing into the unknown can new domains and new performance-related ideologies be found, enabling performance ability to be discovered and re-examined. The Air Plant exhibition is one that is remarkably practical, humble, and respectful to the indescribable and the unknown.

*About Man-Nung Chou:

Man-Nung Chou is a director, writer, and an actor who has worked with the dance, visual art, and art technology domains in recent years. Chou has recently been involved in large-scale events such as Sin City (a media technology-based unmanned theater where she served the role of a screenwriter), The Night of Sodom (a cross-domain media exhibition held by the Taipei Fine Arts Museum), and One Hundred Years of Solitude (shown at the 2016 TNAF where she served the role of a screenwriter).

Descriptions of the pictures:

Picture 1. Riverbed Theatre (Craig Quintero, Carl Johnson, Andrew Kaufman, and Emma Running Lee) (2013–2017). I Stand Naked in the Street with Sleeping Lions, mixed media.

Picture 2. River Lin (2017). A Day in the Life of the Administrator of Yo-Chang Art Museum. Performance, video, dimensions variable.

Picture 3. La Ribot (2014) Beware of Imitations! Mixed media, video installation, dimensions variable.

Picture 4. Wei-Chia Su (2017) FreeSteps–Sense of Place. Video installation, dimensions variable (photograph provided by: Chun-Yi Chang; and sound provided by: Yannick Dauby).

Picture 5. Yen-Hong Liu (2015–2017) Ceylon Houndstongue and the Realms of Land, Water, Fire, Wind, and Space. Video and spatial installation, painting, sculpture, dimensions variable.

Picture 6. Joyce Ho (2017) These Things That Drift Away. Spatial installation, dimensions variable (music provided by: Snow Huang).